Jeff Koons: EQUILIBRIUM:

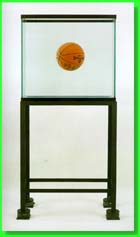

One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (1985)

Marcel Duchamp: Fontaine (1917)

Robert Gober: Untitled (Man in Drain) (1993-94)

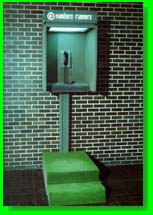

Laurie Anderson: Numbers Runners (1979)

Arman: La Poubelle

de la Colombe d'Or (1969)

Jannis Kounellis: Untitled (1985)

As time goes by I am increasingly convinced that one of the most interesting elements in the exhibition of the Dakis Joannou Collection is the reaction towards it (in this country, that is): the attitudes of all those who praise (in order to flatter), or those who speak words of redemption (by comparing the weight of «American» (1) and «European» art), and those who were woken up abruptly with a bitter taste in their mouth (because they feel excluded). Of course, there were also those who reacted in a more calm and phlegmatic way, uttering a one-word comment: «interesting»! In that sense the exhibition is not only a test of the Collection's logic and cohesion or the collector's competence; it is above all a test of our own «artistic community».

Above all, because if there are any faults with the selection of the exhibits or the (numerically) thin representation of Greek artists, these are «curable» and only concern the owner and not some public museum, whereas our own picture reveals a series of «maladies» which tend to become endemic. Even a cursory glance at the reviews is enough to make one understand what I mean: scared attitudes, a moralizing tone, a sense of isolation, inertia and a lack of ideas are «maladies» to which we seem to have sentenced ourselves. Instead of providing even a morsel of dialogue, most critics seem to agonize over an imminent «control of the local market». But even if it is true —as some people claim— that certain «American critics, managers or museum directors» are after the new collectors in this country, surely the best reaction is neither this sense of persecution nor that sly appeal to the «nobler» ideas —an attitude which, at the end of the day, achieves nothing other than «forcing unlocked gates» and allowing the game to go on without us.

If «Greek art» —or «contemporary art in Greece» if you want— in all its aspects (artists, critics, collectors, magazines), wants to be a serious force, it should re-connect itself to the horizon of ideas and the present; to have something discernible to say, and say it convincingly. In short, to stop relying on «coincidence» and develop «beliefs» instead. I do not mean that it should hasten to attach itself to «fashion» or imitate a reality of images which does not belong to it yet (2), but to generate questions arising from circumstances that are common to all of us. Seeking refuge in the «stability of tradition» is soon exposed as a «trick», since fewer and fewer people believe in «the illusion concerning the world and irony has permeated everything» (J. Baudrillard).

So if there is one thing that scares us more in the exhibition of the Joannou Collection, it is not so much the fact that it shows an art which has lost its «mythical aura» in terms of form —fter all, this had begun with the historical avant-gardes early in this century— but the fact that it looks like our times. Or, more correctly, like the image of the times which is about to come (and is, in that sense, an «American» image): «voyeurism», voyeurismpunches in the retina, an almost incestuous relationship with the media, a frenzied consumerism, an incessant cutting up of idols and symbols, claustrophobic introspection, ironies, playful nothings and all kinds of paradox. In other words, the fragmented landscape of countless contemporary stimuli which leave us speechless at first and to which we become addicted to eventually —like «users of the absurd»— because that's exactly where we end up living. So what is worth discussing is perhaps the way the characters of society and art become the same in these works; we should not treat this solely as a negative example, but also as a reality which may be useful to understand, even slightly.

It would be easy for one to claim that the exhibition «has betrayed the heroic spirit of Duchamp». I would rather say that it reveals a situation which afflicts —or will afflict very soon— anyone who still wants to make art. Besides, we should not forget that it was the European avant-gardes that first rejected the « Of course, we are not obliged to —indeed, we should not— welcome any attempt to turn the present into a deity in a frivolous way, nor remain trapped in «genetic» naiveties. Hence the question remains: what should be our attitude towards this reality? «Apocalyptic» or «integrated»? Should we adapt ourselves to this «aggravation» of experience brought about by contemporary life —or to a quest of a lost «aura»? Adorno and Benjamin were discussing similar issues a few years back; but a lot of things have changed since then, and I don't think that the distinction is as clear as it used to be. This is certainly a good excuse for discussion. Otherwise, to paraphrase Eco, we should eat candy «pretending —thanks to our intellectual powers and our strong control over our senses— that we sense a salty taste».

1. In France —mainly— one can observe this kind of hypocritical, almost schizoid attitude: on the one hand the defenders of «cultural purity» bitterly complain about the oncoming Sixth Republic (the «American» one) êand on the other hand they finance Eurodisney. 2. TThis was probably the aim of the exhibition The Spring Collection, which was nevertheless attacked with unjustifiable wrath by the critics of the «old guard».Yorgos Tzirtzilakis

NOTES

![]() Back to text...

Back to text...

![]() >Back to text...

>Back to text...